Are We Quorate Yet? Return to Bug Signalling

You’re at a cheesy disco – it’s a large room, the lights are down, the music’s loud. But no one’s dancing. Because there are only five of you there and it’s embarrassing. More people arrive and drift across the dance floor self-consciously, but it’s not until you reach a critical density of bodies that feet start twitching and the spirit of Saturday Night Fever is re-born. Many decisions made by bacteria (and other organisms) depend on pretty much the same principles. Are enough of us here yet? Then let’s PARTY!!!!

This is called quorum sensing. And we have two papers in this week’s PLOS Biology that bring us closer to understanding how it works at the molecular level.

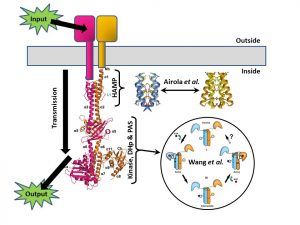

Three weeks ago I wrote a PLOS Biologue blog post that tied together two papers that looked at opposite ends of the signal histidine kinase (SK), a nifty rod-shaped molecule that translates environmental signals from the outside of a bug cell into a phosphate tag on the inside of that cell. The papers showed how it’s all about movement – the HAMP domains clicking from one form to another to signal ON/OFF status, and the business end (the kinase enzyme) swinging right round as the intervening rod buckles.

In that blog post I concentrated on the SK part of the system, telling you expressly to ignore the next bit – the Response Regulator (RR) – and just to think of it as a big “output” arrow.

Now, thanks to a nice bit of serendipity (and two more papers), I can invite you to stop ignoring what happens next, as we’ve just published a pair of papers that focus on a downstream set of molecular movements that determine how the RR integrates signals to help the bug make complex decisions.

First we need to complicate things a bit. We’ve already seen how the SK receives external information, and how its internal movements cause it to activate an enzyme that sticks a phosphate tag onto the RR protein, passing the message on. Two examples of RRs are Spo0F, which then goes on to trigger spore formation, and ComA, which regulates the ability of the bug to take up foreign DNA. Complicated enough? I’m afraid there’s more…

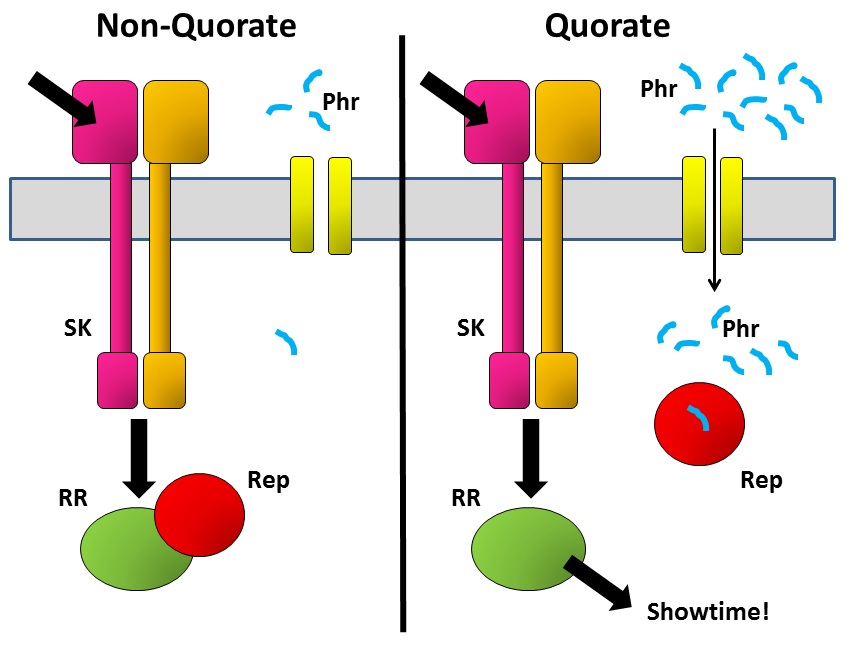

A decision such as whether to form a spore (or not) is a big commitment for a bacterium, so it needs to be able to bring several considerations to the table. One of the ways it does this is by integrating several signalling pathways to give it a final consensus outcome. SK passes on its phosphate tag to the correct RR protein in response to the signal that it has received. But there are other proteins that can then interfere with what RR does next. An example is the Rap family of proteins – some of these inactivate the RR by removing the phosphate that the SK has just put on there, while others bind to the RR and physically prevent it from passing the information on to the next part of the communication chain.

But when the bug makes Rap proteins, it simultaneously makes a tiny matching peptide called Phr. These are just a few amino acids long and are released from the cell into the environment. The bug then imports them back into the cell, where they bind to their specific Rap protein. Why go to the trouble of exporting and then re-importing a peptide? The key is that the amount of peptide in the outside world depends not only on how much that bug secretes, but also on how many of its mates are there also secreting the same peptide. The denser the bug population, the more Phr peptide there is to be imported and to bind to Rap. That’s the quorum-sensing bit.

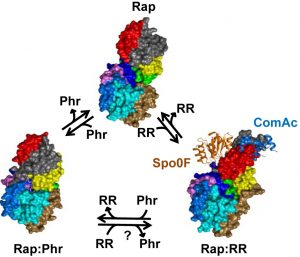

But how does the tiny Phr peptide determine whether Rap does or doesn’t bind to the RR protein? Two new papers, just published in PLOS Biology, tell us exactly how. Research articles by Matt Neiditch and colleagues, and by Francisca Gallego del Sol and Alberto Marina, plus a comprehensive Primer by Marta Perego, now combine with those previous two papers to give us a vivid picture of the dynamism of this whole signalling pathway.

Each paper gives us the detailed structure of a Phr peptide nestling in a slot in its Rap protein, plus a picture of the Rap protein without its Phr peptide. The authors can also compare these to structures of Rap proteins partnered with RR proteins ComA or Spo0F, both previously published in PLOS Biology in 2011 ( ComA and Spo0F papers – by Neiditch and colleagues again). It’s this comparison that reveals what’s going on. Although the free Rap protein has an almost identical shape to Rap that’s bound to an RR protein, the presence of Phr wreaks major structural changes. Once Phr fits into the slot, a distant part of the Rap molecule is re-structured (a phenomenon known as allostery) so that it is incompatible with RR.

This is all interesting enough for those working in the field, but it’s also potentially useful, as these structural studies could give us clues as to how we can manipulate the Phr-Rap signalling system to our benefit. Tricking the bacteria into believing that they’re quorate, even when they aren’t (or vice versa), could be advantageous in many therapeutic and biotechnological scenarios (for example, interfering with quorum sensing could disrupt biofilm formation, an important aspect of the lifestyle of some particularly nasty human pathogens). And given enough beers, most of us will dance on an empty floor.

Parashar, V., Jeffrey, P., & Neiditch, M. (2013). Conformational Change-Induced Repeat Domain Expansion Regulates Rap Phosphatase Quorum-Sensing Signal Receptors PLoS Biology, 11 (3) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001512

Gallego del Sol, F., & Marina, A. (2013). Structural Basis of Rap Phosphatase Inhibition by Phr Peptides PLoS Biology, 11 (3) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001511

Perego, M. (2013). Forty Years in the Making: Understanding the Molecular Mechanism of Peptide Regulation in Bacterial Development. PLoS Biology, 11 (3) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001516

[…] https://blogs.plos.org/biologue/2013/03/20/are-we-quorate-yet-return-to-bug-signalling/ […]