Dude, Where’s My Data?

Q: Where do you look for scientific data?

A: In scientific papers, stoopid!

Sadly, of course, anyone who’s read a scientific paper will know that this isn’t true. Papers actually contain very little raw data, and mostly consist of analysis of the data and discussion of conclusions that can be drawn from the data. That’s OK up to a point, but what if you’re sceptical about the analysis and want to have a shot at doing it yourself? What if you’ve got a nifty idea about using the same data to address a completely different question? The chances are that you’ll have to look further than the paper itself, and, especially if the paper’s old, you may well find that the raw data no longer exist.

The conciseness of the modern scientific paper has presumably arisen historically because a) papers used to be constrained by the space available in old-fashioned printed formats, b) lots of data can obscure the central message of a paper, and c) we didn’t used to have much data anyway. These days we have online journals with unlimited pages, the possibility of substantial supplementary information files, and hyperlinks to robust data repositories, so surely, even with our terabyte-sized datasets, we don’t have to worry anymore?

Well, some fields are pretty good at this – it’s hard to imagine a paper reporting new genomic sequence or a new protein structure not having an accession number that will lead you directly to an online repository (GenBank, PDB, for example) containing the full sequence or coordinates (though I concede that in each of these instances, the sequence/coordinates already represent a level of interpretation of the raw data, which in turn will be less accessible). So although most of the ~300 GenBank entries that carry my name will never be of use to anyone, at least my unborn grandchildren will be able to look at them in puzzled indifference. However, it seems that there are many areas of science where we run the risk of losing most of the data upon which the literature is based.

In a Perspective just published in PLOS Biology, Bryan Drew and colleagues directly test their ability to retrieve the data that underlie one field of endeavour, and find a “massive failure” that they attribute to cultural problems. This piece, “Lost Branches in the Tree of Life”, tackles the specific problem of the “phylogenetic trees” that show the evolutionary relationship between different species (see a previous Biologue post of mine for more about phylogenetic trees).

Constructing trees of life involves the collection of data from organisms that are often rare or exotically located – these are very special data. The resulting publications always present trees as figure panels, but vary as to whether the topological and branch-length properties of the trees, and the sequence alignments themselves, are made available to readers by deposition in a database (e.g. Dryad, TreeBASE). Access to the alignments would allow you to check the original paper’s findings, add your own species, or combine data from different papers to make your own super-tree…

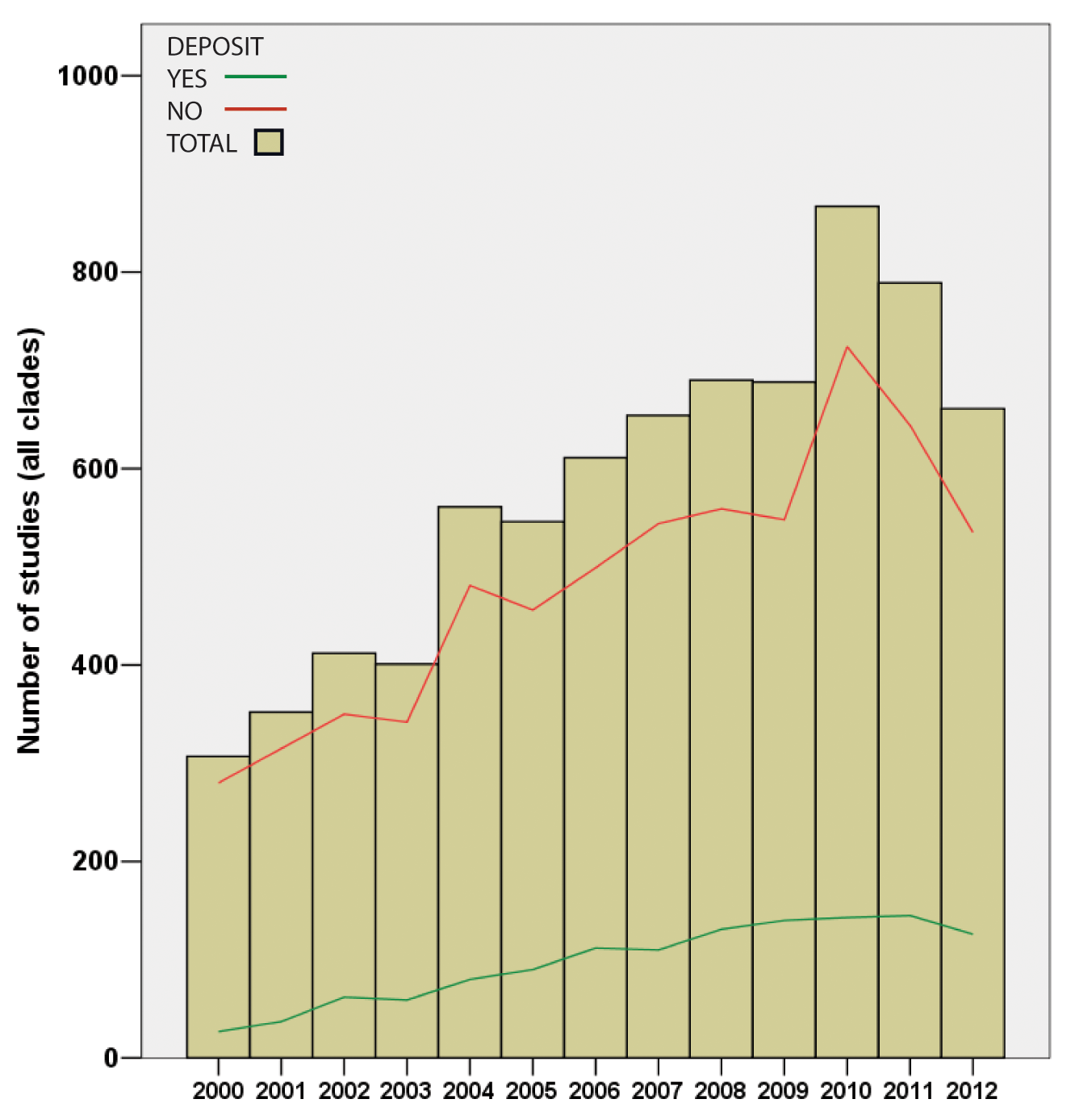

…and it was while making their own super-tree of life comprising nearly two million species that Drew and co-authors noted that of the 7500 papers they studied, data had been deposited for only one-sixth and were available on request from the original authors in a further one-sixth, leaving two-thirds of trees only available as figure panels in the original paper. Lest you assume that the authors were looking back into the Dark Ages before the internet, all papers examined were from the fully digital years 2000-2012. This represents a potentially irretrievable loss of the bulk of the data on which this field rests, and there’s little sign of any improvement.

In a separate Perspective, “Spatially Explicit Data Stewardship and Ethical Challenges in Science”, also just published in PLOS Biology, Joel Hartter and co-authors look at a broader issue of data management, stewardship and sharing across many types of scientific data. They note cultural differences between fields, especially regarding the basic tendency either to share or to guard data. They cover spatially explicit geographical and sociological datasets, and raise the peculiar ethical problems that can arise from the conflict between openness and confidentiality in these fields. These issues are particularly heightened when considering the potentially socially intrusive nature of crowd-sourced and geospatial data. The authors propose a series of measures intended to foster openness while protecting the diverse interests at stake.

Back in June we published a third plea for data availability, from Dani Zamir, “Where have all the crop phenotypes gone?” He also lamented the likely irreversible loss of huge bodies of valuable data generated by large-scale plant breeding programmes devised to map the genetic determinants of desirable (or undesirable) crop traits, and asked “how can we bring about a phenotype sharing revolution?”

In each case, across these disparate fields, we see very low levels of data availability, and it may be that some (many?) fields perform even worse than the dismaying one-sixth that Drew and colleagues saw in phylogenetics. In each instance, the Perspective authors identify the problems as largely cultural, and propose ways forward, asking journals and funding agencies to insist on deposition of valuable and sometimes irreplaceable data.

And it’s clear that journals are indeed spectacularly well-placed to police and incentivise the deposition, tracking, accessibility, and permanence of data associated with the papers that they publish. At the point of acceptance we have the authors over a barrel, and are in a great position to mandate deposition of all data for every paper. And why stop at the data? What about mathematical models and code used for the analysis, both of which are important resources and arguably a formal requirement for reproducibility?

In our guidelines we do insist on depositions (“All appropriate datasets, images, and information should be deposited in public resources.”), and we do try to ensure that the more obvious data are deposited, but I suspect that some slip under the radar. For these we rely on the authors recognising that data sharing is not only good for readers, but is also good for them, enhancing the longevity and (dramatic pause…) citeability of their work.

Want to read more? See other Biologue posts about Open Data and related issues by John Chodacki and Theo Bloom.

Declaration of potential conflict of interest: I’m a PLOS Biology editor and an employee of PLOS.

After collecting, editing & re-publishing cancer genome data (specifically: whole genome copy number screening data) since 2001 trough http://www.progenetix.org and spin-offs, here are some observations:

– only very few data submissions happen actively (without being asked, or after a simple request); certainly in the single digit range

– well configured instructions/templates help (e.g. Affymetrix SNP arrays are kind of overrepresented in GEO due to the Affy expression array templates)

– fancy sites/repositories usually are funded as part of a big project, and die a slow/abrupt death with ceasing of funding/disbanding of the collaboration/the next big thing

– exceptions are too-big-to-fail entities like GEO, sites from forward looking European organisations (SIB!, EMBL), or the ones with somebody crazy nurturing her/his virtual child …

– reasons for no-availability of data are

a) perceived “first mover advantage” (i.e., you publish some part of some bigger analysis, may it be in the works or just in your head)

b) laziness/no benefit from making the data available

c) you really don’t know how to share the data easily

d) dropped onto a server, long gone now

e) lost the floppy (sounds funny, but yes, some of my CGH datasets disappeared that way after publication – not through my fault, though)

f) format?!?!?!?!?!

As a reviewer, I make 2 essential points: 1. that original data has to be made available through a standard source (for our type of data chiefly GEO or ArrayExpress – or possibly our own arrayMap); and 2. that data sources have to be cited, not only mentioned!

Now to the statistics: In my estimate, about 50% of the “old-style” cancer CNA data sets (from chromosomal CGH, Comparative Genomic Hybridization) are available on a per-sample basis (with a large variation in annotation styles …). In Progenetix, we have 20627/35703 cCGH samples from 771/1223 publications (we may miss some, say 10%? But on both numbers). However, numbers are not much better for the genomic array datasets – and worse, and as a different problem, it seems that they are much more homogeneous (i.e. fewer cancer entities).

So my wishes would be:

– an openness towards funding resources, while being critical of short-term goals

– the absolute requirement of all data to be made accessible – i.e. pre-submission deposition and automatic rejection if not, without further evaluation of the manuscript

– citation awareness for resources (data, tissue and software)

Suggestions/comments welcome.

Michael (www.progenetix.org & http://www.arraymap.org)

[…] The conciseness of the modern scientific paper has presumably arisen historically because a) papers used to be constrained by the space available inold-fashioned printed formats, b) lots of data can obscure the central message of a paper, and c) we didn’t used to have much data anyway. These days we have online journals with unlimited pages, the possibility of substantial supplementary information files, and hyperlinks to robust data repositories, so surely, even with our terabyte-sized datasets, we don’t have to worry anymore? […]

To reproduce a study, data is worthless without code and analysis scripts.

Some efforts exist to make the whole analysis available. Bioconductor is a trailblazer (as usual), but given how many people use R for their data analysis, the collection of experimental packages could be better populated: http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/BiocViews.html#___ExperimentData

For all our major projects I make my folks deposit their code at BioC.

For example here: http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/data/experiment/html/Mulder2012.html

I see lots of advantages in doing it:

– it helps us to have clear and reproducible results

– it helps us to avoid embarrassing moments of ‘how did we get to the main figure of the paper again?’

– it helps us to get wider visibility

– it helps me to save time. When people have questions about the analysis it takes me just a second to send them the link to the package.

Florian

You simply can’t beat/guilt people into doing stuff. In the vast majority of cases you’ll be ignored, others will do the least possible and do so grudgingly, and a few will do it well for their own reasons (and they would have anyway).

We need a functional knowledge economy that rewards desirable behaviours (like annotating, structuring and [then] sharing data), and that does so in a career-relevant manner (i.e. no stick-on gonks, branded biros or hand-wavy arguments about visibility).

Rod Page blogged on this (http://iphylo.blogspot.co.uk/2013/09/branches-on-tree-of-life-why-must.html) and I agree wholeheartedly (after years of trying other things): http://is.gd/credit4sharing

Thanks for penning this post, which is a great addition to the debate.

I agree that journals have an important role in promoting reproducible research, but publishers in general have little incentive to maintain data repositories in perpetuity. Moreover, I believe a majority of journal editors don’t see data archiving as a high priority. Some probably don’t even consider it part of their job.

Funding bodies, on the other hand, do have an incentive to make data reusable. Several have policies that mandate grant-holders to deposit their data, but these are hard to enforce.

So the journals and funding bodies have to work together to deliver reproducible research. The funders can provide the resources to build infrastructure necessary for long-term data archiving and retrieval (e.g. http://www.ceh.ac.uk/sci_programmes/env_info.html), whilst the publishers should do more to support their editors and reviewers in enforcing good practice.

I absolutely agree, hence my en passant mention of this important subject that could easily fill a whole other blog post.

I’m sympathetic to your point here, and as a “recovering academic” myself, I live in hope of a credit framework whereby institutions etc can appraise, value and reward these under-appreciated but important activities (not only data deposition but also curation of secondary literature items such as encyclopedia entries and public science communication pieces). However, I’m taking the brutally pragmatic position here (“beat” rather than “guilt”) that we already have the authors, at a point when the data are at their fingertips, over the barrel of accept/reject. This is where we can best capture those data for posterity by using the leverage afforded by the opportunity of publication – a reward that the authors and their institutions are unanimous on. Yes, you could call this blackmail, but this is likely to be the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to capture those valuable data for posterity.

I’d hope that most journal editors do see data archiving as a high priority (as I do). However we have to be realistic as to how much time we can practically devote to policing data deposition as part of the overall process of escorting a paper towards publication. That’s where we need to be able to depend heavily on reviewers and academic editors to insist on the inclusion and/or deposition of all data before publication (or for review, if deemed necessary). I’m not sure that reviewers necessarily bear this in mind. If reviewers insist on deposition of certain data, it’s a simpler job for the editors merely to check that deposition has occurred and accession details are included in the MS.

I think journals really can (and should) beat people into sharing their data. They hold the keys to the publication gate, and authors must put their data on a public archive before their paper is allowed through.

This does require extra curation of each manuscript, but the net benefit to the community is well worth it. The journals I work on (Molecular Ecology and ME Resources), which mandate and enforce sharing, have data from almost 900 articles on Dryad.

These datasets are now increasingly used by readers to check (and sometimes challenge) the results in the paper. This is what making science ‘self correcting’ really means, and it can’t happen without data sharing.

public data sharing will need:

1. enforcement by journals BEFORE publishing the articles

2. funding agencies ensuring long-term funding to run & sustain data repositories

3. common format for codes/scripts submission (biologists don’t understand this but this not only is necessary but essential)

4. big & famous scientists, who regularly publish in scn journals, mandate that not a single paper goes out of the lab door unless 100% of the raw data along with software and codes/scripts gets deposited in a public repositories

lets not be presumptuous. science is v competitive and what brings rewards and grants/grant renewal is not to be a good samaritan and submit all your data/scripts/codes but publications in good journals. unless the attitude towards publications and the excessive weight given to publications change, nothing is going to happen. it all stems from that. binay

[…] “Dude, where’s my data?” by Roli Roberts […]

[…] , Bryan Drew et al and Dominique Roche et al all in PLOS Biology with associated blog posts from Roli Roberts and Emma Ganley (editors on PLOS Biology). And then read Cameron Neylon’s post ‘Open is a state […]

[…] it also raises critical—and significantly less discussed—questions about how such openness is being done, and is playing out, in practice. In other words, how—in terms of making things not only available, but also usable and […]

[…] As we’ve discussed before, an open access paper is enhanced enormously if it’s directly linked to the openly available data from which it was constructed. Data availability enables replication, reanalysis, new analysis, interpretation, or inclusion into meta-analyses, and facilitates reproducibility of research. […]

[…] to all of these endeavours is the availability of the data that underlie studies, which a study in PLOS ONE shows to vary massively between scientific disciplines, being best in […]