This Week in PLOS Biology

In PLOS Biology this week, you can read how plant pathogens convert flowers to leaves, how gut bugs might suppress bowel inflammation, and how endocytosis pathways talk to each other.

Parasites are often able to modify the behaviour of their host to benefit their own lifecycle. A new study by Allyson MacLean, Saskia Hogenhout and co-workers set out to discover how the bacterial plant parasite phytoplasma does just this. Phytoplasma relies on leafhoppers to spread and propagate it. They identified a protein, SAP54, which is produced by the bugs and manipulates the floral transcription programme, transforming flowers into leaves and resulting in a sterile plant which is a perfect nursery for leafhoppers to lay their eggs.

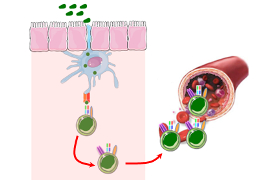

We know that the bacteria living in our gut affect health and disease, but many of the mechanisms still elude us. These are particularly pertinent questions for sufferers of conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which are associated with gut microbial imbalance. Guillaume Sarrabayrouse, Francine Jotereau and colleagues found that a newly identified class of regulatory T cells of the human immune system can be activated by a bacterium commonly found in the gut. These regulatory T cells can then tone down inflammation reactions, which are prevalent in conditions such as IBD. Interestingly patients with IBD are known to have fewer of these bacteria and these findings could have therapeutic implications. Read more in the accompanying synopsis.

Endocytosis is the process by which substances (such as proteins), or sections of the cell membrane are imported into the cell. The substance is ‘engulfed’ into the cell through several alternative pathways which involve invagination of the membrane to form spherical protein-encapsulated vesicles. Most commonly, a molecule called clathrin is involved, but recently more has been understood about clathrin-independent pathways. In a research article this week, Natasha Chaudhary, Robert Parton and colleagues discover substantial cross-talk between two of these non-clathrin pathways; the caveolar pathway and the CLIC/GEEC pathway.