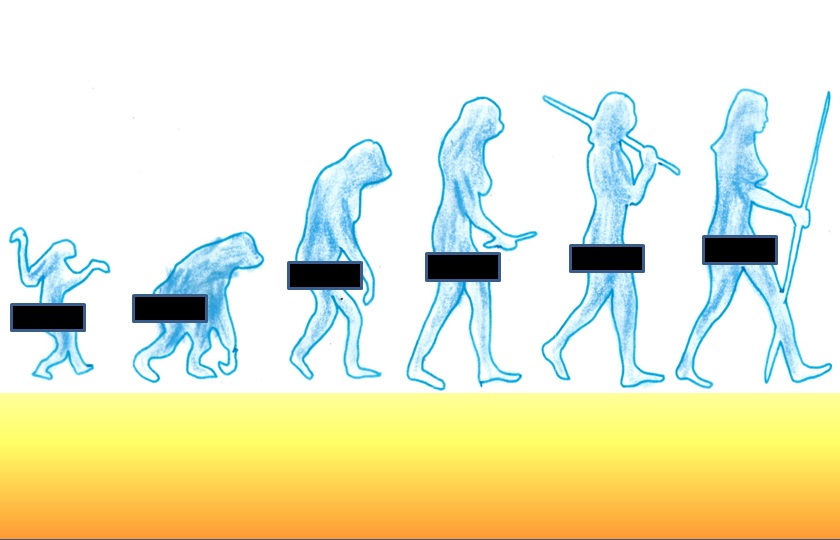

Why Do Scientists Ignore Female Genitalia?

Humans have an odd attitude to genitalia. Indeed, more than 90% of you are reading this blog post merely because I put the word in the title. A new study shows that biologists, being human, also have an odd attitude to genitalia.

Sexual reproduction occurs across most of the animal kingdom, allowing us to shuffle our genes at the poker table of life. And in many cases this occurs by direct physical interaction between two sexes, usually by transfer of sperm from the male to the female via a neatly compatible USB interface known as genitalia.

Unlike the USB, where compatibility is in everyone’s best interests, because of sex’s central role in the evolution of sexual beings, every aspect of it is subject to subversion by strong selective forces, and therefore liable to rapid and apparently capricious change – courtship behaviour, plumage, and even the molecular mechanism that determines whether you’re male or female. But what about genitalia?

Genitalia are also subject to spectacular change, and the assumption is surely that, in the case of two such intimately apposed organs, male and female genitalia should co-evolve, each driven by those motivations that tend to drive other aspects of sex – the male to sow his oats as widely as possible, and the female to be choosy as to how she apportions the costly provisioning of a future infant.

The study of the evolutionary biology of animal genitalia is indeed a vibrant field, but apparently it has a problem. A big one. A paper just published in PLOS Biology reports a survey of hundreds of recent papers and finds that the field is massively biased towards study of male genitalia – almost half of the studies only address males, with most of the remainder looking at both sexes. The bias varies according to the evolutionary model involved, with an explicitly female-driven model (cryptic female choice) being even-handed, but the others being dominated by male-only studies (red):

So what are the reasons for this bias? The authors look at three of the more obvious explanations:

a) Biological: Female genitalia don’t vary enough to drive evolutionary change.

b) Practical: They do vary, and do drive evolution, but are devilishly hard to study.

c) Intellectual: They do vary and drive evolution, and can be studied, but the field is intellectually blinkered.

The authors use examples to argue that the first two explanations are invalid, and that the field is intellectually hobbled by a blind assumption that male genitalia indulge in all sorts of evolutionary shenanigans, but “too often the female is assumed to be an invariant container within which all this presumed scooping, hooking and plunging occurs.” Author Malin Ah-King says “We found that the most plausible explanation for the bias is the enduring assumptions about the dominant role of males, and unimportance of variation in female genitalia.”

But where do these assumptions come from? Although the tabloid stereotype of the scientist may be of a monkish, geeky male boffin whose real-life encounters with female genitalia are tragically infrequent, clearly many scientists are women. Barron and co show that the gender of the senior author on these papers doesn’t correlate with the genital sex bias, so that simple explanation can be excluded.

The authors are studiously restrained when it comes to speculating as to what might lie behind this bias in the field. Luckily as a blogger, I’m free from academic constraints and can indulge in some cod sociology. Here are some (obvious and intertwined) suggestions:

a) Even in the 21st century there’s a bizarre societal squeamishness about female genitalia that doesn’t apply to male genitalia. This plays out in the media in odd and prurient ways, including a sex bias in the severity of taboo words and a game of “chicken” as to how much one can get away with saying. Could this background be subliminally affecting career choice, study design, funding, or publication decisions? Surely as free-thinking scientists we’re above this sort of thing?

b) It’s easy to imagine a situation, say 50+ years ago, where an influential evolutionary role for females would have been an intellectually challenging concept for a heavily male-dominated and culturally sexist academe. Could this reluctance to acknowledge evolution’s equal opportunity policy have been propagated, via the inherently conservative conduits of textbooks and undergraduate teaching, down the decades?

c) Fields can be dominated by the ideas of one or two highly persuasive individuals or schools of thought. Perhaps one or two big-shots, possibly influenced by one or both of the above cultural issues, or possibly out of a feeling of confidence in their own correctness, put forward models for genital evolution that are still able to hold sway with 21st century men and women?

The likely answer is that it’s a little of all of these – a mixture of cultural milieu and historical contingency (a bit like evolution itself). Can this field be rescued? The authors take us on a whistle-stop tour of some of the more spectacular instances of the role of female genitalia in evolution, and Ah-King hopes “that this analysis can increase the awareness of gender bias and its impeding effects on research, and thereby enable a broadened understanding of genital evolution in the future.”

Read the paper:

Ah-King M, Barron AB, & Herberstein ME (2014). Genital evolution: why are females still understudied? PLoS biology, 12 (5) PMID: 24802812

[…] Why do scientists ignore female genitalia and sexual reproduction? […]

[…] Why Do Scientists Ignore Female Genitalia? – PLOS BiologueType: article Credit: Roli Roberts, adapted from Rudolph Zallinger. Humans have an odd attitude to genitalia. Indeed, more than 90% of you are reading this blog post mer […]